Rust Lulz: Godbolt assembly exploring without crate limitations, in Visual Studio Code

Compiler Explorer (often known as “Godbolt”) is a very convenient tool for exploring the disassembly of Rust programs.

It has a significant limitation: it can’t disassemble projects depending on external crates.

After some hairpulling, I’ve found how to achieve Godbolt functionality in Visual Studio Code, without such limitation.

In this (quick) article, I’ll show how to do it.

Content:

Setup

Install the Disassembly Explorer VSC extension.

This extension is based on the Compiler Explorer project, so we’re actually going to obtain Godbolt’s core functionality, without the limitations.

Create a project, with some routines using an external crate:

$ cargo new disasm

$ cd !$

$ cat >> Cargo.toml << 'TOML'

rand = "*"

[profile.release]

debug = true

TOML

Since we’re exploring the release version, we need to tell cargo/rustc to keep the debug symbols (optimizations won’t be affected), otherwise, it won’t be possible to map the source file to the disassembly.

Now let’s write the source code:

$ cat > src/main.rs << 'RUST'

const F32_SIGN_BITMASK: u32 = 0b1000_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000;

const F32_EXP_BITMASK: u32 = 0b0011_1111_1000_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000;

fn gen_random() -> u32 {

rand::random()

}

pub fn gen_gruf_1() -> f32 {

let rnd = gen_random() % 2;

if rnd > 0 {

-1.

} else {

1.

}

}

pub fn gen_gruf_2() -> f32 {

let rnd = gen_random() % 2;

(rnd as f32 - 0.5) * 2.

}

pub fn gen_sav() -> f32 {

let rnd = gen_random();

f32::from_bits((rnd & F32_SIGN_BITMASK) | F32_EXP_BITMASK)

}

fn main() {

let gruf_1 = gen_gruf_1();

let gruf_2 = gen_gruf_2();

let sav = gen_sav();

println!("{}", gruf_1);

println!("{}", gruf_2);

println!("{}", sav);

}

RUST

(ignore the logic of the program, as it had been written purely for the lulz)

Preparation of the assembly file

Generate the assembly output of the project:

$ cargo rustc --release -- --emit asm=src/main.S

This will store the disassembly where needed by Disassembly explorer (without specifying the filename, it’s stored as target/release/deps/<project_name>-<hash>.S).

In order to get a more readable disassembly, we can process it through c++filt, which demangles the names:

# Run `cargo clean` if the ASM was previously generated, but the source code wasn't changed.

#

$ cargo rustc --release -- --emit asm=/dev/stdout | c++filt > src/main.S

Compiler Exploration :)

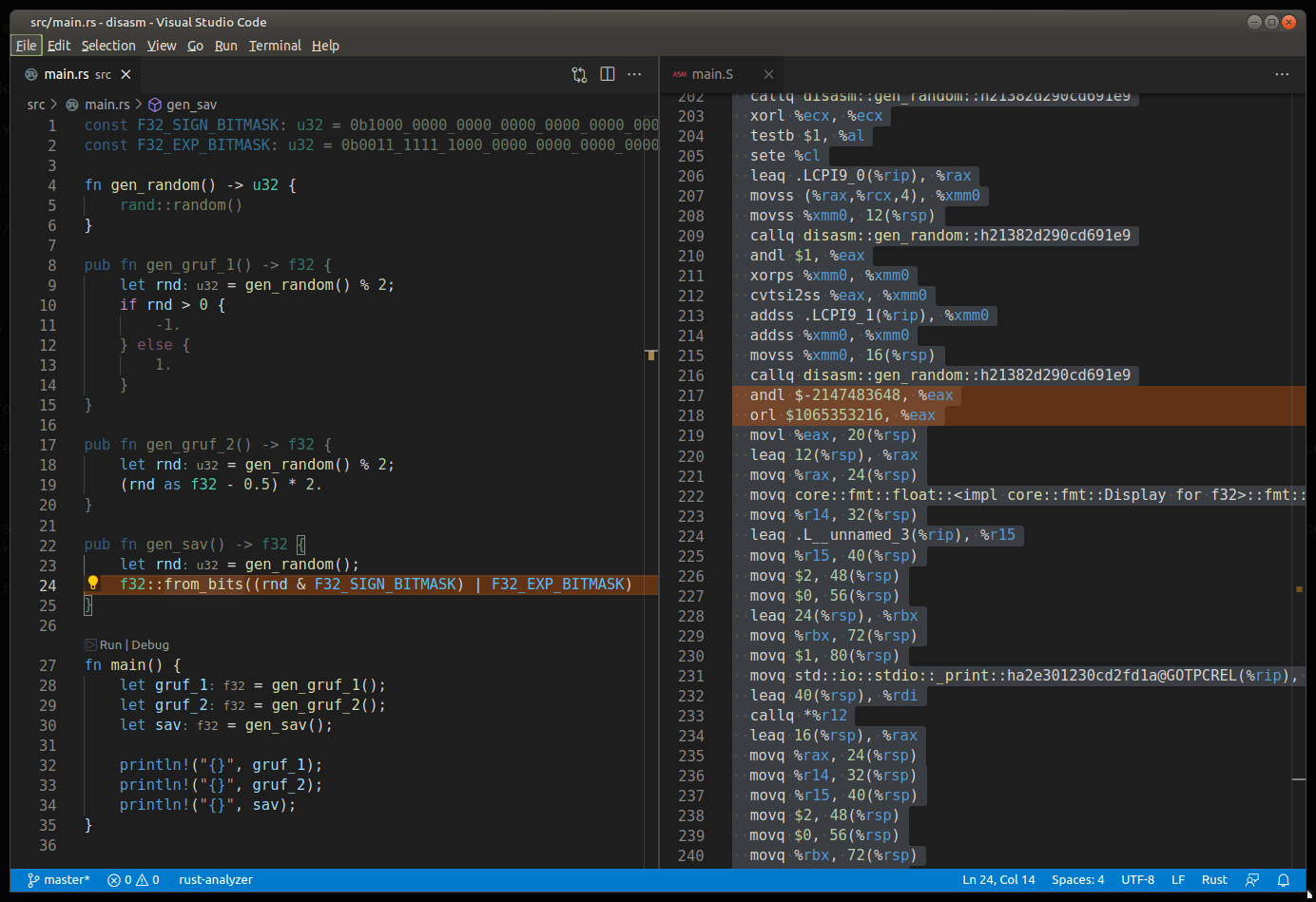

Now open main.rs in VSC, and execute the command Disassembly Explorer: Show. Enjoy!

Inlining notes

Inlining and interleaving are compiler features hostile to disassembling, as they typically makes it impossible to map the source code to the assembly with precision; therefore, don’t expect Disassembly Explorer to do miracles 😬

Isolating a function can help the process; a strategy to do this is to make the function public in a library module in the same crate; while the binary invoking the function may still inline it, the disassembly generated for the library itself will have the function isolated.

Cargo supports a crate that is both a binary and a library; the simplest way is to just add a src/lib.rs file, move/copy the function in it, and then generate the ASM for the library (cargo rustc --release --lib -- --emit asm...).

Conclusion

The effort to identify target code a disassembly is certainly a minuscule part in typical tasks involving assembler (e.g. optimizing code). However, making the process smooth and more intuitive, makes it easier to focus on the task 😌

I also find important that Rust gathers first-class tooling; having extended Compiler Explorer functionality available… is just cool!